The Thomas Block’s Future Is Dim

18 January 2022

The Thomas Block (William H. Wharff, architect, 1904) occupies 181 feet on Center Street

(photo: Daniella Thompson, January 2022)

In August 2021, an application for a 17-story mixed-use development at the intersection of Center and Oxford streets was submitted to the City of Berkeley’s Planning Department. The proposed project includes a 181-foot stretch on Center Street that is currently occupied by the historic Thomas Block, designed by the architect William H. Wharff in 1904 and remodeled for the John Breuner Company in 1925.

In a State of California Primary Record prepared in 2015, the Thomas Block was deemed a Contributor to the Shattuck Avenue Downtown Historic District:

Built in 1904 and altered in 1925, much of the historic fabric has been preserved. The proportions and materials of the two-story fa�ade continue today to serve as a clear example of an early-twentieth-century commercial design in the downtown core.

The Thomas Block is part of a setting of mostly historic buildings that form the primary corridor of commercial buildings lining Shattuck Avenue and the transit center that connects the city with the University of California campus. From 1908 [editor’s correction: from 1876] through 1938, the Berkeley train depot sat at the end of this block on Shattuck Avenue. The Thomas Block was developed when the station was active in the city, and when Center Street was the main thoroughfare between the station and the University.

How the building received the name Thomas Block is a yet unsolved puzzle. The name first appeared in print in the Berkeley Daily Gazette issue of 9 May 1904, where it was announced:

Work of construction is now in full blast on the Thomas block, on the south side of Center street, between Oxford street and Shattuck avenue—a building that gives promise of being one of the most important business structures in the city. The commodious block will contain ten large stores on the lower floor and 50 rooms that will be devoted to flats and offices on the second floor. It is estimated that the entrrprise will require an expenditure of $28,000

Berkeley Daily Gazette, 9 May 1904

On 17 June 1904, the San Francisco Call reported:

The Republican Club of Berkeley has taken the first step toward rounding up all the Republicans of Berkeley before the next campaign by engaging rooms in the new Thomas block on Center street, where headquarters will be established.

Charles E. Thomas (San Francisco Call, 21 June 1901)

Could the new building have been named after Charles E. Thomas, a young Republican politician who had just completed several years in the role of Berkeley Town Clerk, also serving at times as secretary of the Board of Trustees and of the Board of Education?In June 1901, on the occasion of his marriage, the San Francisco Call described Charles Thomas:

The groom is one of the most prominent and popular young men of Berkeley. He graduated from the university in 1899 with the degree of B. L. During his college days he was the recipient of many student honors, holding the offices of speaker of the Students’ Congress, editor in chief of the Daily Californian, and president of the Associated Students. He also made a reputation as a student of unusual brilliancy and promise. Since his graduation he has been admitted to the bar, but has not practiced. He has been connected with several business enterprises, which he has conducted with marked success. In the last municipal election he was elected Town Clerk by an overwhelming majority.

After leaving his municipal job, Thomas managed the Realty Title Company, whose office was located in the Thomas Block.

Classified ad (Oaklamd Tribune, 27 July 1904)The building’s name appeared again on 27 July 1904, when a classified ad for the Wawona, an establishment offering rooms and apartments in the Thomas Block, was published in the Oakland Tribune. (The Wawona was replaced by the Campus Apartments in the early 1920s, followed by the La Loma Apartments in 1926.)

Kellogg School (William Warren Ferrier: Berkeley, California)The owner of the land since early 1879 was the Town (later city) of Berkeley, which erected its first school building on the site. S.D. Waterman describes the purchase of five lots and the construction of the school in his book History of the Berkeley Schools (1918).

Waterman described the site as follows:

Strawberry Creek at this time [1879] ran down Allston Way from Fulton Street across Shattuck Avenue. The railroad crossed the creek by means of a trestle on the east side of Shattuck, and there was a bridge and a walk for ordinary travel on the west side. The creek crossed Oxford Street near Center and cut diagonally across to the corner of Fulton and Allston. The channel of the creek was in the middle of the street and there was a raised walk for “foot travelers” on the south side of Allston.

When the Town Trustees completed the culvert for carrying the water of the creek [in 1895], the school lot had a double frontage—Center Street and Allston Way.

When the school lot was purchased there were but three houses on the block;—one, owned by Dr. J. S. Eastman as a residence, since moved to the Oxford frontage,—a cottage toward Shattuck Avenue owned and occupied as a residence by John Boyd, known as “Boss Baggage Buster of Beautiful Berkeley,”—and a small building occupied by Mikkelsen and Berry as a tailoring establishment. An apple orchard covered the rest of the block. [...]

On January 29th, 1879, the plans of Samuel and J. C. Newsom were adopted, and after due formality in advertising for bids the contract was let to Mr. George Embury for $3365. As there was no money available for immediate use, Messrs. J. L. Barker, H. Bartlett, C. D. Dornin, H. A. Palmer and F. K. Shattuck agreed to furnish the money as a loan. When the building was completed, it was named “The Kellogg Grammar School.”

The school was named after Professor Martin Kellogg, seventh president of the University of California and a member of Berkeley’s first Board of Education.

The school buildings and grounds took up more than a third of the block, as can be seen in the 1890 Sanborn fire insurance map below. By 1894, the school grounds had expanded to more than half the block.

Kellogg School buildings & grounds in the 1890 Sanborn map

Kellogg School buildings & grounds in the 1894 Sanborn mapBy the early 1880s, Kellogg Grammar School had become Kellogg School, including high, grammar and primary divisions. When Berkeley High School moved to a new building on Grove Street in 1901, the old school building became home to the Public Commercial School.

Public Commercial School buildings & grounds in the 1903 Sanborn map

Public Commercial School in 1904 (George Pettitt: Berkeley, the Town and Gown of It)In order to make way for the Thomas Block on Center Street, the Commercial School building was moved south to face Allston Way. That school ceased to exist in 1909, and the building was taken over by the California School of Arts & Crafts. An adjacent classroom building was transformed into an undertaker’s establishment.

The Board of Education owned the Thomas Block from the time it was constructed until it was sold to Oakland furniture merchant Louis J. Breuner in 1925.

Thomas Block (pink) in the 1911 Sanborn mapThe Thomas Block was designed by William Hatch Wharff (1836–1936), a prolific San Francisco architect and Civil War veteran who moved to Berkeley in 1899 and was in demand for designing various buildings in the old downtown. His best surviving building is the landmark Masonic Temple at 2105 Bancroft Way.

The builder of the Thomas Block was the Lindgren-Hicks Company, engineers and contractors, who specialized in reinforced concrete construction and would soon take part in San Francisco’s post-earthquake rebuilding, touting their earthquake-resistant work on the 19-story Humboldt Savings Bank and the Fairmont Hotel.

Ad in American Builders’ Review, 4 August 1906The son of a Swedish builder, Charles J. Lindgren (1859–1913) immigrated to the U.S. in 1879. After learning brick masonry in post-fire Chicago, he made his way out west. In 1889, Bakersfield, California suffered a disastrous fire, and Lindgren settled there, taking advantage of the rebuilding boom. There he met Lewis Albert Hicks (1868–1945), an Indiana-born civil engineer and pioneer in steel-reinforced concrete who was then working as assistant engineer for the Kern County Land Company.

In 1900, Lindgren and Hicks joined forces, establishing themselves on Benvenue Avenue in Berkeley as macadam and cement contractors. The following year, they expanded their business by purchasing John A. Marshall’s cement contracting firm. In late 1902, they signed a contract with Phoebe Apperson Hearst to construct the Hearst Greek Theatre, promising to have it ready for President Theodore Roosevelt’s commencement address in May 1903.

Julia Morgan, a prot�g�e of Mrs. Hearst’s, had recently returned from her architectural studies in Paris and was supervising the Greek Theatre construction project as an employee of John Galen Howard. Hicks and Morgan would interact again in 1906, while reconstructing the Fairmont Hotel. Shortly afterwards, Miss Morgan would design a reinforced concrete house for Hicks at 2311 Piedmont Avenue (now the Chi Psi chapter house, it has been greatly altered).

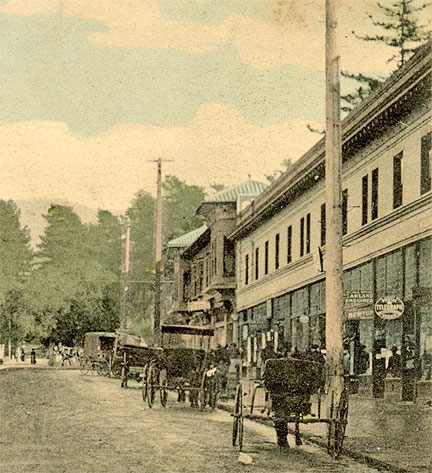

Center Street c. 1907 on a colorized postcard, with the Thomas Block on the rightCharles Lindgren moved to Fresno in 1903, there to begin a new building spree, but his partnership with Lewis Hicks endured until 1907.

The Thomas Block c. 1907 (courtesy of Anthony Bruce)Construction of the Thomas Block was supervised not by the Lindgren-Hicks Co. but by the realtor Simcoe S. Quackenbush, who, like the builders, moved his office into the new building to stimulate sales. For a while, the building was called the Lindgren-Hicks Co. Building, but after the partnership’s breakup it was renamed the Lewis A. Hicks Co. Building.

The Thomas Block, aka Lewis A. Hicks Co. Building, c. 1908 (courtesy of Anthony Bruce)By the 1920s, Lewis Hicks, too, was gone, having moved his office to 2735 Durant Avenue, across Piedmont Avenue from his home. When the City of Berkeley put the Thomas Block up for sale, Louis J. Breuner’s bid of $90,000 was the highest.

Breuner immediately remodeled the building in the Mediterranean style, but as the State Primary Record affirms, “the proportions and materials of the two-story fa�ade continue today to serve as a clear example of an early-twentieth-century commercial design in the downtown core.”

Note: About 16 years ago, then-LPC commissioner Robert Johnson wrote a landmark application for the Thomas Block but withdrew it when the property owner expressed strong opposition.

Copyright © 2022 Daniella Thompson. All rights reserved.