Oscar Wilde, Joseph Worcester, and the English Arts & Crafts Movement

An Historical Footnote

Leslie Freudenheim17 July 2008

While researching my next book (about Joseph Worcester and San Francisco’s Swedenborgian Church), I came across two exciting troves of previously unpublished information. The first is a lecture series on the role of art in life given by Joseph Worcester in 1882; these talks were retrieved from storage by the Swedenborgian House of Studies Library in April 2008 and are not yet catalogued.1 The second treasure consists of correspondence in the Bancroft Library between Joseph Worcester and William Carey Jones about another lecture series, this one to be presented by artists chosen by Worcester. For those interested in the growth of the English Arts & Crafts Movement in America, its manifestations in California, and the influence of Joseph Worcester in the Bay Area, this information is eye-opening.

Part I. “Role of Art in Life”: A lecture series given to “a Club” in 1882.

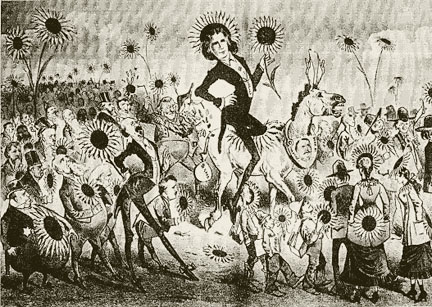

Oscar WildeWhen the eccentric British playwright/poet Oscar Wilde spoke in San Francisco on March 27, 1882, the press lambasted him for his clothing as well as for his remarks.

Wilde’s American tour began in New York, where young Oscar Wilde had been the center of a maelstrom of scandalous incident and publicity from the moment of his arrival in early January 1882. There was a sudden exaggerated vogue of sunflowers, lilies, and Japanese parasols—all of which were said to evoke Wilde’s enthusiasm. Newspaper reporters outdid themselves in ridiculing the twenty-eight-year-old “lecturer”; cartoonists pounced upon him with a fervor less brutal than gleeful; women draped themselves about the new “lion”; and the few men who found something sensible and telling in Wilde’s advice and pronouncements on art and decoration were unheard for the most part in the paen of masculine denunciation. The costume adopted by young Wilde, which included short breeches, long silk stockings, and a shoulder-length haircut, was hailed with horror and amazed contempt by young dandies educated to long tight trousers, high stiff collars, and full mustaches.2

“The Modern Messiah,” Keller’s cartoon of Oscar Wilde in the San Francisco Wasp, 31 March 1882 (San Francisco Museum)Ambrose Bierce, best known for his Devil’s Dictionary and Joseph Worcester’s neighbor on Russian Hill, was one of Wilde’s most vitriolic critics:

The ineffable dunce [Wilde] has nothing to say and says it [...] with a liberal embellishment of bad delivery, embroidering it with reasonless vulgarities of attitude, gesture and attire. There never was an impostor so hateful, a blockhead so stupid, a crank so variously and offensively daft. Therefore is the she fool enamored of the feel of his tongue in her ear to tickle her understanding.

Bierce’s denunciation continued:

The limpid and spiritless vacuity of this intellectual jelly-fish is in ludicrous contrast with the rude but robust mental activities that he came to quicken and inspire. Not only has he no thought, but no thinker. His lecture is mere verbal ditchwater—meaningless, trite and without coherence. It lacks even the nastiness that exalts and refines his verse. Moreover, it is obviously his own; he had not even the energy and independence to steal it.3

Between August and October 1882, shortly after Oscar Wilde had spoken in San Francisco, Worcester presented a series of lectures in which he subtly attacked Wilde and the whole concept of art for art’s sake espoused by Wilde and his friend, the painter James McNeil Whistler.

Swedenborgian Church, San Francisco (photo: Jim Karageorge)

For those readers unfamiliar with Joseph Worcester, he was not only the clergyman responsible for building the Swedenborgian Church at the corner of Lyon & Washington Streets in San Francisco, an icon of the Arts & Crafts Movement (1892–95); he was also an amateur architect and the man most responsible for the design of: 1) what may well be the first American bungalow (it was constructed as his own home atop a hillside in Piedmont in 1878); 2) four unpainted, brown-shingle Arts & Crafts houses on Russian Hill erected between 1887 and 1889 (two are still standing); 3) at least one of painter William Keith’s three studios; and 4) the Stratton house in Berkeley, about which the Strattons wrote:

If our house was not planned in the fear of the Lord, it surely was planned in fear of the late Joseph Worcester [...]. Worcester’s quiet disapproval or clear acceptance of any feature proposed had in it for us something of a pope’s finality.4

The Stratton house, 67 Canyon Road (The House Beautiful, May 1916)According to Charles Keeler, a poet, ornithologist and advocate of the Arts & Crafts style for Berkeley homes, Worcester’s “...word was law in the select group of connoisseurs of which he was the center.”5 To put it simply, Worcester was the person many considered and still consider most responsible for the widespread growth of the inexpensive, brown shingle Arts & Crafts home in the Bay Area.6 These newly uncovered documents demonstrate that Joseph Worcester not only affected the region’s architecture but that he was also a central player in its art scene.

Rev. Worcester’s Piedmont cottage (detail from a painting by William Keith)In The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), Oscar Wilde’s Lady Bracknell admits, “We live, I regret to say, in an age of surfaces.” In these newly uncovered lectures at the Swedenborgian House of Studies, Worcester castigates Wilde’s philosophy of art for art’s sake and argues instead for art that is useful, uplifting, spiritual and derives from nature:

“...we shall be cultivating that which I believe and shall try to show you to be, something mindful, useful to a full & complete human life [art].”

“...forms of art are expressions of human feeling, and, instead, the inspiration of art has become simply a sensuous delight in its forms with a constant deterioration in the beauty of those forms.”

“Human feeling has a message to deliver: the form of its expression is its message...”

“To think plainly even a little thought is a beautifully figurative way of inculcating the modesty & sincerity from which all good work is done & expressing revolt against the pretense, the vulgarity, the extravagance and falseness of modern art” [this is a criticism of Oscar Wilde, Whistler and the Aesthetes]

“It recognizes the power and beauty of the little tho neglected things of nature, and the quickening effect upon art of faithful effort to copy them. It suggests the vulgarity of the mere possession of anything however beautiful.” [Worcester is probably referencing William Morris’ 1882 admonition: “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful” although both statements were made in the same year.]

“...the loving care and use of the fewer simple goods/gifts of life honestly gathered brings to the soul more of richness and sensibility than does an abundance of the costly and rare valued chiefly in the possession.”London’s central role for the art world was recognized on both American coasts. In 1882, the prominent Bostonian architect Henry Hobson Richardson met William Morris in London, while concurrently Joseph Worcester praised London as a center of art. In 1883 Worcester wrote his best friend, the painter William Keith, about his plans to visit Europe.7 Whether or not Worcester actually traveled in Europe to meet his brother, who lived in Italy at the time, or acquired his extensive knowledge of the European art scene by reading books, meeting foreigners and attending World Fairs, by 1882 Worcester evidently knew a lot about the art and architecture of Greece, Italy, and England, as demonstrated in these lectures on the role of art in life. These talks also reveal, if there ever was any doubt, how completely Joseph Worcester was a Ruskinite, how thoroughly he understood the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s principles (closely related to those of the Arts & Crafts movement), and how committed he was to transmit these ideas to the Bay Area.

Worcester never uses the term “Arts & Crafts” in these talks because he wrote them six years before the Arts & Crafts movement was so named—in 1888. However, he was well acquainted with the movement’s emphasis on nature, its call for a return to the countryside, for things handmade rather than machine made, as well as the growing British insistence that furniture, architecture and art should be meaningful.

Worcester disliked Wilde and the aesthetic movement because it championed art for art’s sake and denied that art could have any moral value. Ten years later, when planning the Swedenborgian Church he still disliked the aesthetes:

I hope our plan will not be too aesthetic, but my artist friends are much bent on making it so. They want to build a little church, but a pretty church I do not think I could stand; I prefer the little congregation in the bare hall.9

Interior, Swedenborgian Church, San FranciscoIn his lecture dated Sept. 15, 1882 Worcester considers London the art center of Europe:

If we were to pull up stakes and go where we pleased we should certainly, with the fever of culture upon us, move towards the great cities of Europe and, judging you by myself, should gravitate, perhaps somewhat circuitously towards London—the metropolis of the modern world, [where] I believe we should find [...] an exaltation of the simple beauties [...] of this everyday world [nature]. We should find a freedom from pretence & affectation, an absence of vulgarity.

However, not all of London meets Worcester’s standards. He singles out the Pre-Raphaelite artists for praise while criticizing artists principally interested in affectation and appearances—the Aesthetes. Similarly, although Worcester seems to have been reading British art journals published as early as 1850 he did not accept everything espoused in those publications; instead he discriminated carefully among their Arts & Crafts theories as is revealed in these lectures.

For example, in a direct slap at Oscar Wilde, who belittled sincerity: “A little sincerity is a dangerous thing, and a great deal of it is absolutely fatal.”10 Worcester praised the Pre-Raphaelites for their fundamental sincerity:

They called themselves “pre-raphaelite” because they found in the wings of Lippi’s angels and the columbines of Perugino’s gardens that loving and exact study of minute things which gave them a sense of sincerity, and which they missed in the breadth and ease of later work.11

Worcester admired their honesty and directness so much that in this same talk he expressed his desire to establish a “new Brotherhood for the maintenance of those principles” in the Bay Area such as the Pre-Raphaelites had established “thirty years before” in England.

Beata Beatrix by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery)Although he admired their camaraderie and the formation of a brotherhood of friends who wanted to share ideas, he abhorred the overly saccharine sensibility of some of the Pre-Raphaelite artists’ work. It was their collaborative circle and their dedication to an art that sprang directly from truth, sincerity and nature that attracted him to the Pre-Raphaelites and made him wish to set up a Brotherhood that will offer its members

...mutual encouragement in the practice of these principles as expressed by a recent writer:Plainly to think even a little thought, to express it in natural words which are native to the speaker, to paint even an insignificant object as it is, and not as the old masters or the new masters have said it should be painted, to persevere in looking at truth and at nature without the smallest prejudice for tradition, [...] They called themselves “pre-raphaelite” because they found in the wings of Lippi’s angels, and the columbines of Perugino’s gardens that loving and exact study of minute things which gave them a sense of sincerity, and which they missed in the breadth and ease of later work.12This was published in 1850 in The Germ—a short-lived publication (4 issues), where it was referred to as a sonnet. Worcester knew that publication well enough to cite from it, confirming his familiarity with cutting edge thought in the artistic world.

Worcester prepared this series of talks on “The Role of Art in Life” for “a Club” [which Club remains a mystery] in 1882; six years later, in 1888, he organized a series entitled “Talks on art by the Artists.”

Part II. “Talks on Art by the Artists”: A lecture series delivered in 1888.

Joseph Worcester’s correspondence with William Carey Jones13 about this second lecture series indicates he knew many artists, as well as architects, and in this letter to Jones we see he had a sense of humor about their foibles (and his own):

All last evening the impossibility [...] and absurdity of what I had undertaken kept coming up to me causing little explosions of laughter—the idea of managing such an unmanageable set of creatures as our artists. But Mr. Keith and Mr. Wores came in spite of the rain, and they have just gone, and, they are fired with the desire to do it. Now my doubt is how far the artists fire is to be depended upon.14

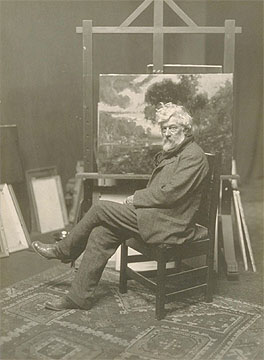

William Keith (The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley)And although William Keith was his closest friend, Worcester, freely expressed to Jones his doubts as to Keith’s ability to face an audience and present a lecture on his art.

Mr. Keith [said] I should just like to stand up before those professors and tell them that they don’t know the first thing about art. His misgiving came in this form, – I could tell them all I have to say in five minutes. Of course, he thinks so, but the five minutes would be a very long one, [...] and he would consume an hour before he had fairly begun his talk.

[...] I will ask him tomorrow to select the slides from which he will talk. I told him he must begin with the question: What ought one to look for in a picture? He agreed...15

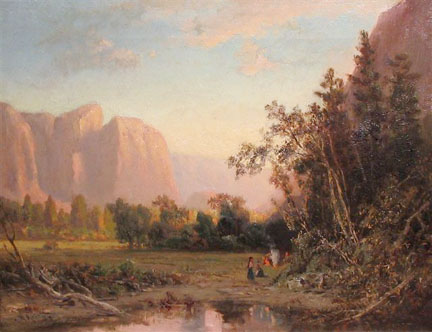

“Yosemite, Cathedral Rocks” by William KeithWorcester’s artist friends, like most artists, were used to wielding a paintbrush not words; therefore they were reluctant to give a lecture in his series. However, we can be certain that at least one of these talks discussed with Jones was actually given because in later years William Keith recalled the event with horror as a way of explaining why the talk he was about to give to the Sorosis Club16 would consist of personal recollections only and would not be an art historical analysis and he refers to the horrors of lecturing “...some years ago, before the University of California. It was a lecture on Art.” Keith complains he had to consult books and suffered anguish in the delivery.17

“Yosemite, Bridalveil Falls” by Thomas Hill, 1873When one artist after another expressed doubt about being able to lecture in his series, Joseph Worcester went to “Tom” Hill (the use of Tom instead of Thomas suggests Worcester knew this prominent artist personally) as well as to Emile Carlson and Theodore Wores.

These 1888 lectures were to take place in the “Assembly Hall,” which may have been in the Bacon Art and Library Building at UCB.18

College of Letters, assembly hall stereograph (The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley)To make the lectures more appealing, Worcester tells us, William Kingston Vickery, of the art dealership Vickery Atkins and Torrey, had agreed to organize a “lantern exhibition.”

Worcester’s friendship with Jones, who later served on the advisory board of the Phoebe A. Hearst International Architectural Competition, may have helped Worcester’s lobbying efforts to make John Galen Howard supervising architect during construction of the university in the early 1900s, but that’s another story. These lectures demonstrate Worcester’s ability to befriend, and undoubtedly influence, artists as well as architects in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Notes

1. As an Adjunct Research Scholar at Swedenborgian House of Studies I requested several boxes in storage be retrieved. Most (99.9%) of the materials received were sermons. The other .1% discussed above must be processed and catalogued before being made generally available; however I have transcribed them for my use and am excerpting sections in this article.

2. Lois Foster Rodecape, “Oscar Wilde Visits San Francisco,” California Historical Society Quarterly, June 1940. News coverage of Wilde’s American tour actually began the previous January, and, as Rodecape pointed out: “During the winter months there were published in the Wasp and in other California publications occasional jingles about Wilde and the Aesthetes; a popular song entitled ‘Oscar Dear’ was received with condescending humor in the city’s gay spots; and the slang of the moment included such supposedly Wildean expressions as ‘too utterly utter,’ ‘just too too,’ and ‘do you yearn?’ ”

3. Bierce published these nasty comments on Wilde as part of his weekly column, “Prattle,” in The Wasp, just after Wilde spoke in San Francisco, March 27, 1882.

4. I am very grateful to Anthony Bruce, Executive Director of the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association (BAHA), for pointing out the Strattons’ comments to me. Writing in The House Beautiful in 1912, Professor and Mrs. Stratton confirm Worcester’s influence on the design of their house: “Our house was unquestionably shaped in a perceptible measure by the work of a local architect of uncommon taste [...] He was a Swedenborgian minister [...]”

5. For Keeler’s praise of Joseph Worcester, see his San Francisco and Thereabout (1902) , pp. 41–42.

6. Building with Nature: Inspiration for the Arts and Crafts Home (Gibbs Smith Publisher, Nov. 2005) introduction and conclusion and throughout text.

7. “A family story of long ago from letters of William and Mary Keith,” Keith-McHenry-Pond Family Papers; Banc Mss CB 595 miscellany V, 1–10, II & III 1883–1893.

8. Ibid., Letter, Monday, May 5, 1883. Mary McHenry Keith writes from Europe: “At noon he [William Keith] came home lookg much happier—cause—letter from mr. Worcster, seemed to me one of the best he’d ever written. Spoke of coming here for a few weeks. Made W[illiam] crazy w joy at the thought of it….Tell mr. Worcester, if he cant come this summer to come next fall and go with us to Italy; visit his brother etc. and we could all come home together.” The fact that Joseph Wocester’s brother was living in Italy in 1883 lends credence to my belief that Joseph could also have lived in or at least traveled to Europe.

9. Joseph Worcester to Alfred Worcester, March 1, 1892, in Swedenborgian House of Studies compilation of letters to his nephew, Alfred Worcester.

10. I wish to thank Alan Thomsen, an expert in the field of historical Arts & Crafts literature and a member of the San Francisco Swedenborgian Church for pointing out that these lectures are an attack on Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetes.

11. The name Pre-Raphaelites comes from their admiration of works of art prior to Raphael and their dislike for later art work.

12. Worcester is quoting the sonnet by Pre-Raphaelite poet William Michael Rossetti (brother of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti) from which the Pre-Raphaelites’ principles derive. That sonnet prefaced the Pre-Raphaelites’ literary magazine The Germ—Thoughts towards Nature in Poetry, Literature, and Art and later Art and Poetry: Being Thoughts towards Nature Conducted Principally by Artists, published in only four issues in 1850. Worcester cites the entirety of this sonnet except one phrase, which reads: “this was the whole mystery and cabal of the P.R.B.”

13. William Carey Jones (1854–1923), administrator, professor, and founder and first director of the School of Jurisprudence at the University of California, may have asked Joseph Worcester to organize this series; in any case, Worcester sought approval for his plans from Jones. Their correspondence is housed in the Bancroft Library BancMs CB 536. Joseph Worcester had left his position as Reverend of the Swedenborgian Church (then meeting in Druids Hall) and had moved to Piedmont in 1876. From Piedmont, only a short distance from Berkeley, he maintained close ties with several professors at the University.

14. June 20, 1888 in BancMs CB 536, Box 2, folder 49, subseries 1.1, Incoming Correspondence, 1884–1923.

15. Ibid. Jan 24, 1888.

16. Sorosis, a professional women’s association, was created in 1868, a year after the founding of Pi Beta Phi, the first national secret society for women.

17. Keith-McHenry-Pond Family Papers, BancMssC-B-595, Scrapbook V: 1890-95, p.595

18. Henry Douglas Bacon gave the building which he dedicated in 1881 and many other gifts to UCB; he lived in Oakland and died 1893. I could not locate any reference to an “Assembly Hall” at UCB in 1888, so Bancroft library staffer David Kessler suggested the Assembly Hall might have been inside the Bacon Library and Art Gallery and supplied the attached photograph.

Leslie M. Freudenheim is the author of Building with Nature: Inspiration for the Arts and Crafts Home (Gibbs Smith, November 2005); Capital Drawings: Architectural Designs for Washington, D.C., from the Library of Congress, edited by C. Ford Peatross with the assistance of Pamela Scott, Diane Tepfer, and Leslie Freudenheim (The Johns Hopkins University Press, October 2005); and Building with Nature: Roots of the San Francisco Bay Region Tradition, co-authored with Elisabeth Sussman (Peregrine Smith, 1974). Leslie is currently a Research Associate at the Swedenborgian House of Studies and a Research Fellow at the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley.