Berkeley Observed

Memorial Stadium—controversial from the start

Susan Cerny

1930s postcard from the BAHA archives2, 9 & 12 September 2003

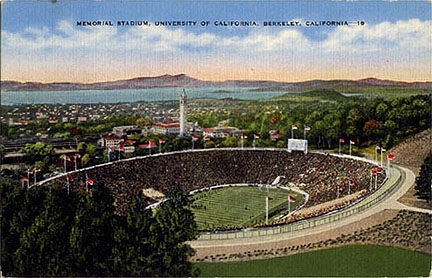

Completed in November of 1923 in time for the Big Game between Stanford and Berkeley (which Cal won 9-0), Memorial Stadium in Strawberry Canyon was built amid intense controversy.

When initially proposed and promoted in 1921, the stadium was planned for a two-block area located east of Oxford Street between Allston and Bancroft Ways just south of Strawberry Creek, where the Sports Facility Complex now stands.

The front page of the Oakland Tribune for Sunday, 25 Sept. 1921, announced:

U.C. Stadium Details are Given Public: Structure Will Be Erected Between Allston Way and Bancroft.University president David Barrows and Assistant Comptroller (and future U.C. President) Robert Gordon Sproul were enthusiastic about the location in a promotional brochure produced to raise funds for the undertaking.

Barrows declared that this “Stadium, with dimensions that slightly exceed the great Coliseum of Rome [...] will represent the physical and moral basis which our education seeks to lay for the intellectual training that is superimposed [...] how great a spiritual significance it assumes [...]”

Sproul described the proposed stadium as “a splendid addition to the Phoebe Hearst Plan” and “an architectural monument ranking with the greatest structures of all times,” hailing the project as “a prime necessity,” “a continuing source of income,” and “a memorial, dedicated to those Californians who died in the War of Nations that civilization should not perish.”

Then plans changed, and Strawberry Canyon was chosen instead, inspiring opposition from a group of architects and one landscape architect who had worked on the initial stadium plan.

The four architects were prominent graduates of U.C. Berkeley’s School of Architecture and included: William G. Corlett (class of 1910), Henry H. Gutterson (class of 1905), Walter T. Steilberg (class of 1910), and Walter H. Ratcliff (class of 1903). The landscape architect was Bruce Porter.

The group wrote an open letter, published in the form of a pamphlet, to the “Students, Faculty, Alumni and Friends of the University of California,” asking them to write the Regents to “reconsider their decision [...] brought upon them an undue pressure of haste [...]” and pointing out that they had donated funds for a stadium on the Allston/Bancroft site and not in Strawberry Canyon.

Further objections included in the pamphlet:

The pamphlet concluded:

- The location of the stadium in Strawberry Canyon would prevent its being the central unit of a large athletic establishment.

- “Considerations of Transportation and Accessibility” pointed out the obvious that it was far from a steep climb from where there were already several transportation lines.

- “Architectural Considerations” included the size of the canyon in relationship to the size and scale of the stadium; “the axis of the canyon is east and west while the stadium would need to be north and south to keep the west sun out of the players’ eyes.”

- The development would forever destroy the natural beauty of the canyon and “the inspiration that nature has placed there.”

Every architectural problem is one of location, design and construction. We believe that in this instance a grave error is being made.

Memorial Stadium between College Avenue and Panoramic Hill

(postcard from the Anthony Bruce collection)Where once Strawberry Creek turned in its leisurely course to the bay, man has reared a great concrete bowl where more than seventy thousand people may gather to watch athletic contests and to see their sons and daughters graduate from college walls.

Robert Sibley

The Romance of the University of California, 1928Before Memorial Stadium was constructed, Strawberry Canyon was Berkeley’s most popular place to experience nature. It was a place for contemplation, bird-watching and walking in the woods, and a rustic neighborhood grew up on Panoramic Hill overlooking the canyon.

Although the north side of the hill had been subdivided in 1888, it was not until 1909, when the entire hillside was purchased by Warren Cheney, that the hill began to be developed for houses. Cheney was the former editor of the literary magazine The Californian and owner of the Warren Cheney Real Estate Company.

Professor Charles Rieber’s house was one of the earliest built on the hill in 1904. The house, designed by noted architect Ernest Coxhead, is unique in that it wraps around the base of the hill where Panoramic Way intersects with Canyon Road. A sprawling shingle-style house, it was designed to blend with its natural rustic surroundings and look out over the canyon.

As Panoramic Hill developed, many rustic yet sophisticated shingled houses were built, including One Canyon Road (1905), also designed by Coxhead for Frederic Torrey, a San Francisco art dealer. Other houses on the hill include several by Julia Morgan, Walter Steilberg, Walter Ratcliff, Bernard Maybeck, and even one designed by Frank Lloyd Wright at 13 Mosswood Lane.

Most of the houses were built by university professors who wanted to live in the country, but within walking distance of the campus and downtown. To this end, developer Cheney built the elegant classic staircase, Orchard Lane, in 1909, and several footpaths and connecting staircases for pedestrian convenience.

Even today, the hill has a remote unspoiled quality in spite of its proximity to the stadium and the bustle of the streets below.

The special ambiance of this neighborhood is best experienced by walking, using the footpaths and staircases. Early 20th century homes of various sizes can be seen through a thick garment of greenery. A walking tour guidebook, giving the date and name of architect when known, is available for a small fee from Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association.

The proposal to build the stadium into Strawberry Canyon provoked opposition not only from the neighborhood, but also from architects, the director of the California Academy of Sciences, and the directors of the Greek Theater.

Professor Rieber, whose house was expressly designed to look over a wilderness, was so upset that he moved away.

The university paid no attention to complaints, calling them “selfish,” planned the stadium in Strawberry Canyon, and then declared in the 1923 Blue and Gold (Volume 49, page 42):

Surrounded by the natural beauties of Strawberry Canyon, the Stadium will be a monument which every Californian will be proud to have a part in the building.

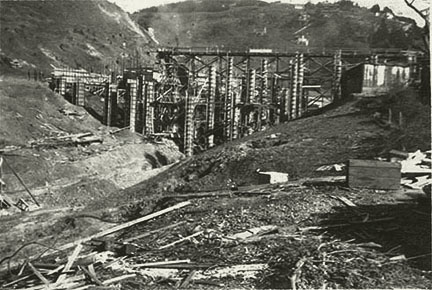

Memorial Stadium under construction (photo: BAHA archives, courtesy of Richard Wesell)The building of Memorial Stadium was an enormous undertaking that began in November of 1922 and was rapidly completed by November of 1923. Building Review magazine reported that the first phase of the project was the excavation of approximately “[...] 280,000 cubic yards of material by hydraulicking [sic] and by steam shovels [...] it was an extremely interesting sight to see.”

The stadium was financed by subscription from alumni, faculty, and students. For each $100 dollar donation, the subscriber would receive script worth $10 per year for ten years toward the purchase of tickets to the football games.

The reason given for the selection of the Strawberry Canyon site over the previously announced alternative closer to downtown was that this was land the university already owned and therefore would not have to pay out additional funds for its purchase.

Just why the University hadn’t considered this before announcing and soliciting funds for the other site remains a mystery.

Neighbors feared that the stadium would be used for events other than university football games and events such as graduations, but were assured by Robert Gordon Sproul that the stadium would be used only for school-related activities—which proved to be the case for many decades thereafter.

Then, suddenly in 1972—and despite regulations prohibiting use of university facilities by commercial enterprises—the U.C. Regents approved a three-year contract with the Oakland Raiders.

Though the Raiders deal was the first violation of Sproul’s promise, it wasn’t to be the last: rock concerts came next.

The new crowds—a different mix altogether from the more sedate university student and alumni community—overwhelmed the city, its services, and especially the areas closest to the stadium.

After two years, the City Council cried foul, passing a resolution disapproving of the leasing of Memorial Stadium for commercial use.

The era of professional football games and other events in the stadium finally ended, but only after much public complaint.

To paraphrase a familiar quotation: If we don’t learn from the mistakes of the past we are bound to repeat them.

The photograph of the building of Memorial Stadium was discovered at Urban Ore in an old family photo album that had discarded. Among the many photos were six of the stadium under construction. If you have such photographic treasures, don’t throw them away. Donate them to the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association or Berkeley Historical Society.

These articles (1, 2, 3) were originally published in the Berkeley Daily Planet.

Copyright © 2005–2019 BAHA. Text © 2003–2016 Susan Cerny. All rights reserved.