Berkeley Square: from transport hub

to urban core18 August 2008

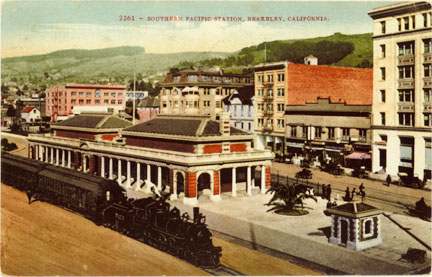

The Shattuck Ave. & Center St. intersection seen from Berkeley Square in the late 1910s. The Southern Pacific train station is on the right. (Picturing Berkeley: A Postcard History)Between Center Street and University Avenue, Shattuck Avenue forks into two branches, enclosing an island intersected by Addison Street. The rectangular northern portion of this island is called Shattuck Square; the wedge-shaped southern portion is known as Berkeley Square.

The entire island served as the Berkeley terminus of the Central Pacific (later Southern Pacific) Railroad since 1876. It was Francis Kittredge Shattuck and his neighbor James Loring Barker who provided CPRR a free right-of-way through their lands along Shattuck Avenue, donating 20 acres for a station and rail yard and topping it off with a $20,000 subsidy in order to induce the railroad to build a branch line from Oakland to central Berkeley.

For the first 30 years, the train depot at the southern tip of the island was a very minimal affair. But as the university campus began acquiring a dignified appearance under the leadership of John Galen Howard, Berkeley’s civic leaders wanted the train station to follow suit, and they seized the opportunity to lobby SP’s president, Edward H. Harriman. In 1899, Harriman had financed and accompanied a scientific expedition to catalog the flora and fauna of the Alaska coastline. Among the participants in the Harriman expedition was Berkeley naturalist and poet Charles A. Keeler. When Keeler and University of California president Benjamin Ide Wheeler found themselves at a dinner attended by the railroad tycoon, they convinced him that Berkeley deserved a better train station.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire and the attendant burgeoning of East Bay population served as a powerful incentive to expedite the project, and on 29 May of that year, the San Francisco Call announced: “The railroad company has the plans for a $50,000 depot in Berkeley in abeyance, but gives hope to Berkeley folk by saying that when the press of emergency measures has passed, construction work on the new depot will certainly be begun.”

The SP station in 1909. Some people believe it was designed by John Galen Howard.A week later, surveyors began work on the site. By mid-July, workers were laying out a line of three large grass plots for a park that would stretch from University Avenue to the site of the new depot. In September, SP management sent a letter to the Berkeley Chamber of Commerce, announcing its intention to convert its suburban trains from steam power to electricity, which would make the SP service “‘equal if not superior’ to any other in this section.” The unnamed “other” was Borax Smith’s Key Route, whose Oakland-San Francisco ferry service, inaugurated in October 1903, connected to downtown Berkeley via electric trains.

The proposed station design made its press debut on 25 September 1906, when the San Francisco Call announced: “The Southern Pacific is about to begin the construction of a new passenger depot at Berkeley. When completed it will be one of the most beautiful railroad stations in America, its artistic lines conforming with the general trend of the architecture of the magnificent buildings designed by M. B�nard of Paris for the Greater University of California. It will combine with comfort and usefulness a beauty of design and a richness of finish. The plans are the creation of the engineering department of the Southern Pacific under the direction of J.H. Wallace, assistant chief engineer, and D.J. Patterson, architect.”

The Southern Pacific station opened in April 1908 and was demolished thirty years later. (Picturing Berkeley: A Postcard History)When opened on 9 April 1908, the station was widely considered to be the most elegant depot in the state. Consisting of twin wings clad in dark red brick with light buff terra-cotta trim, the 158-foot-long station was crowned by a red tile roof with copper cresting and cornice. A colonnade ran along its north, west, and south sides. The 23-foot-high waiting room featured a mosaic tile floor, white enameled wainscoting, massive ceiling beams of weathered oak, and a large open fireplace.

So beautiful was the station that some architectural historians suspect it was the work of John Galen Howard. This belief may have some basis in fact, since blueprints of the station were found among Howard’s office papers.

Southern Pacific’s park circa 1926. The “For Lease” sign portends the end of green space on Shattuck Square.The park behind the station lasted less than twenty years. The city was far more interested in revenue-generating buildings than in open space at its core. In 1926, three elegant commercial buildings—all designed by the San Francisco architectural firm of James R. Miller and Timothy L. Pflueger—were erected on Shattuck Square. The middle building still bears the name of Roos Bros., the clothing store that had been a fixture on Shattuck Avenue since 1912.

The station itself was destined to be replaced by another apparel store a decade later.

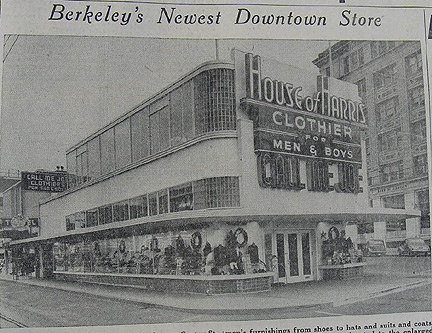

Beginning in 1923 and for over five decades thereafter, Call Me Joe was one of Berkeley’s best-known men’s and boys’ clothing stores. Founded by transplanted Brooklynite Joseph William Harris (1897–1978), the original store was a 10-by-14-foot leased space at 2000 Shattuck Avenue. A born entrepreneur and a tireless promoter, Harris made his business flourish from the get-go, and several expansions followed in quick succession.

Joe Harris standing in front of his newly completed store, which replaced the SP station in 1938. (courtesy of Billie Jean Harris D’Anna)In 1938, after changing transportation patterns left the SP depot idle, L.C. Hall of Mason-McDuffie’s leasing department proposed demolishing the station and using the land for business sites. Harris was the first tenant on Berkeley Square. His new Call Me Joe was a one-story, Streamline Moderne “daylight” store, topped by an enormous neon sign. Midway up the building, a flat-roofed, sheltering overhang resembled the brim of a straw hat, while glass-block corners and clerestory windows provided daylight illumination from above. Continuous expanses of glass display windows wrapped around the store. The architect was John B. Anthony, who two years earlier had designed the Harris residence, now Berkeley’s best-known Streamline Moderne building, at 2300 Le Conte Avenue.

Adjoining Call Me Joe to the north was a store building incorporating the new SP ticket office. According to the Architect & Engineer of California, this building was designed by San Francisco architects Hertzka and Knowles, although no evidence has been found to indicate that their plans were utilized. This building, clad in brick and yellow tiles, was completed in 1939 and still stands, although altered. Adjacent to the north, a small reinforced-concrete store building, erected somewhat later, features an interesting WPA Moderne fluted fa�ade.

The Berkeley Chamber of Commerce/Travel Service building and Mademoiselle boutique were completed in 1941. (BAHA archives)The final two buildings to go up on Berkeley Square were completed in 1941 and retain to this day their angular Moderne appearance and original details, complete with finely fluted stucco walls, upswept entrance marquee, horizontal rows of windows, and glossy black tile trim. The northernmost building, two-stories tall, originally housed the Berkeley Chamber of Commerce on the second floor and the Berkeley Travel Service on the ground floor. For many years, a large vertical Greyhound sign adorned the fa�ade. Next door is a lower store building that originally served as the home of the elegant boutique Mademoiselle and is now a dental clinic.

The Berkeley Chamber of Commerce/Travel Service building and the adjacent store building retain their original appearance. (photo: Daniella Thompson, 2008)The new Call Me Joe store was so successful that only a year after its opening it was necessary to add a second floor. The remodeled store opened on 9 December 1939 under the name House of Harris. On the eve of the reopening, the Berkeley Daily Gazette carried a special 8-page section devoted exclusively to the store. According to the Gazette, “The upper floor is the most daylight store of men’s clothing in the country. It is almost entirely surrounded with windows.” The store’s 20,000 square feet of floor space displayed a $100,000 stock of clothing purchased especially for the Christmas season and “offering a metropolitan city store variety of everything from shoes to hats pertaining to men’s dress.”

The expanded store was renamed House of Harris. (Berkeley Daily Gazette, 8 December 1939)The active Joe Harris found time for serving as director of the Chamber of Commerce, the Berkeley Downtown Association, and the Berkeley Traffic Safety Commission, besides his ongoing involvement with various clubs and the Boy Scouts (House of Harris included a Boy Scout post).

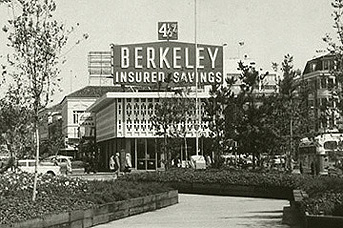

Berkeley Square in the 1940s (courtesy of the Berkeley Historical Society)For several years, the old “Call Me Joe” neon sign was kept below the new “House of Harris” sign on the fa�ade, but after Harris sold the store in the 1940s, “Call Me Joe” was retired. The store continued to do well. In 1958, requiring more space, it moved to a larger building on the site of the old Fischel Block at the northwest corner of University and Shattuck Avenues, where it continued in business until 1976. The Berkeley Square store was to be remodeled for the Berkeley Savings and Loan Association, but the cost of converting the structure to conform with the building code proved prohibitive. Only 18 years old, the distinctive Streamline Moderne ship-like store was razed and replaced with an attractive ’50s glass-curtain building, whose second floor was clad by precast concrete decorative sunscreen panels. Above the flat roof, a gigantic neon sign advertised the interest rate paid by the S&L.

Berkeley Savings & Loan (BAHA archives)This building, too, was destined not to survive. In 1965, the institution’s name was changed to American Savings. A 1970 alteration removed the perforated concrete panels and added an ugly overhanging marquee, which required special variance from the city council, since the zoning law prescribed a horizontal distance of not less than two feet between a marquee and a curb line. For thirty long years, the American Savings building was a blight in the heart of downtown Berkeley. In 1999, the site was acquired by the Kaplan test-prep organization. The Kaplan building, renovated by Kava Massih Architects, helped restore a measure of attractiveness to Berkeley’s core.

Berkeley Square in 2008 (courtesy of Steven Finacom)

This article was published in the Berkeley Daily Planet on 21 August 2008.

Copyright © 2008–2022 Daniella Thompson. All rights reserved.